| MARK WINTLE |

| Mark Wintle, an angler for thirty-five years, is on a quest to discover and bring to you the magic of fishing. Previously heavily involved with match fishing he now fishes for the sheer fun of it. With an open and enquiring mind, each week Mark will bring to you articles on fishing different rivers, different methods and what makes rivers, and occasionally stillwaters, tick. Add to this a mixed bag of articles on catching big fish, tackle design, angling politics and a few surprises. Are you stuck in a rut fishing the same swim every week? Do you dare to try something different and see a whole new world of angling open up? Yes? Then read Mark Wintle’s regular weekly column. |

BITE DETECTION First, find your fish. Get ’em feeding, and then catch ’em. But how do you know when you’ve got a bite? And is the method that you favour always the best one?

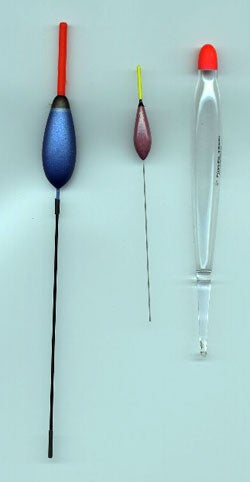

Does it matter that much? Over the decades, there have been many debates – from Walker versus Bernard Donovan, Walker versus Clive Smith, and most recently Len Arbery versus Stef Horak. In the past, it was the match anglers versus the specimen hunters, now it seems to be the traditionalists versus the modernists, or it just mechanical aids versus touch legering? Who is right, or are they all right? One thing is certain, and that is whatever method is used some bites will not be detected. There is more to this than simply the efficiency of bite detection; how much concentration is required? How sustainable is that concentration? Does the bite detection method selected work under different conditions, and how important is the design of the end rig? There are so many methods of bite detection that it is not possible cover all of them in detail but I hope to cover the majority. One thing I learnt from watching fish take a floatfished bait many years ago is that it is surprising how many bites are completely undetected, and furthermore it takes an amazingly vigorous bite to register at all. It is hardly surprising that we occasionally reel in to find a fish on the end. Floatfishing Several simple factors determine the design of a float tip. Can I see it in the prevailing conditions? Is it sufficiently buoyant to support the terminal tackle dependent upon whether factors such as the weight of the bait, the strength of the current/undertow or the bait is dragging on the bottom? How much inertia must be overcome to show a bite? And finally, is it sensitive enough to register a bite? In favourable conditions it is possible to use fantastically sensitive floats; look at those used in pole fishing, yet these would be worse than useless for fishing on the Severn in a gale.

Visibility is often the biggest challenge of these factors. There are a number of options that can help. Different coloured tips perform better in different conditions. An open sky backdrop with lots of ‘white’ water is often best tackled with a blacktopped float. Yellow can work well against the green of vegetation, whilst orange/red are probably the most versatile. One way of increasing visibility without compromising too much sensitivity is to design the float tip so that it is not solid, either using vanes like a dart or with a hollow tip that lets in water through a hole. For night fishing, I have no hesitation in recommending the use of Starlites or Betalites though you may have to design a float to carry one. From a rig point of view, the best way to improve detection is to try to match the size of float according to the conditions. There is usually some sort of compromise required between obtaining good presentation, casting distance, bite detection and visibility. The float rig that is likely to be least sensitive is where a laying-on type set-up is used. Some rigs such the lift float and windbeaters address this whereas simply fishing way over depth may only register the sail away bites. As it is not my intention to write a book on floatfishing at this point it’s time to move onto the methods available for legering and free-lining. Legering Whilst some anglers pondered improvements on the bobbin, others turned their attention to rod top indication. The tips of rods were often made from built cane in the late fifties. But whalebone was also available. By shaving it down as fine as possible better bite indication might be obtained. This was the first quivertip developed around 1956. When Jack Clayton tried to make one a year or two later he overdid the sanding to get a floppy tip that was further developed into the first proper swingtip. Solid fibreglass was also becoming more available about this time and, having reached the limits with built cane, Peter Stone and others were making improvements to the design of quivertips. Known as ‘Donkey tops’, due in part to the amount of donkey work required to sand one down, these tips remain popular to this day with the sophistication of interchangeable tips and the use of carbon fibre in addition to glass. Further refinements followed with the development of the springtip in the mid seventies. All of these tip-based indicators have a limitation in that there is limited movement in the tip, up to about a foot at most, and the fish may encounter increasing resistance, but they remain popular and successful. Night use is aided by affixing Starlites or betalights to the tip.

Bobbins Touch legering Line watching

Concentration Watching the Bait Conclusions I certainly don’t have all of the answers, and I guess no one ever will, but the figuring out will keep us all interested for many years to come. Next week: ‘Pleasure Fishing Commercial Fisheries’ |