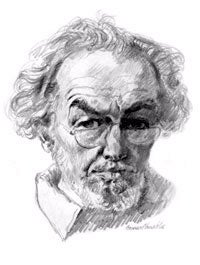

An Essay Review by Barrie Rickards A STREAM OF LIFE by BERNARD VENABLES Medlar say: Barrie Rickards: Two people dominated the second half of the Twentieth Century in our world of angling: Richard Walker and Bernard Venables. RW died too young, whereas BV lived to the ripe old age of94, and was able to leave us a substantial autobiography “A Stream of Life” published by The Medlar Press in 2003 only a short time after his death. On the face of it they were poles apart in terms of angling philosophy: I shall examine this idea from the RW standpoint in my developing biography of him; but here I want to look at this and other facets of the great BV. ‘A Stream of Life’ is not an angling book in the ordinary sense. Indeed, angling is barely mentioned in the first third of the book, and in the rest is really the story, or stories, of his involvement in various sagas such as the birth of Angling Times and Creel, not to mention Mr Crabtree.

One of the themes running through the book is that things – almost everything – is changing for the worse. You might at first dismiss this as the ranting of a man in his 90’s, but the first part of the book really justifies his standpoint. He is well aware of the poverty around, only too well aware in fact, but he points to values and the pace of life and the rightness of doing things in a certain way. He regrets the passing of milk churns and the fact that delivery was by dipping your jug into the churn. Things did pass more slowly than he, a Londoner, perhaps appreciated. I was still dipping the family jug in the churn in the late 1950s and early 1960s. There is still one street in Cambridge that has gaslights, although they are self-igniting now and need no lamplighter. I remember lamplighters and I am far from my 90s. Other elements in the early part of the book strike rather too many chords with me; perhaps it is true of all long-time anglers that they chased loach and bullheads, that they found and marvelled at fossils, that they had close encounters with massed sparrows nests under the eaves, that they saw trout in a mysterious stream before they knew what they were (see my book ‘Fishers on the Green Roads’!), that primary school is a prison and Grammar School little better. I even had a teacher called Sammy, though not as nasty as his Sammy; we both enjoyed cross-country running. Perhaps the major theme or thread of ‘A Stream of Life’ is that, to him, art is of fundamental importance, shaping all, shaping his life. He came to the end of his life much as he started it, burning with enthusiasm for art but not far short of poverty. Everything he did, everything he learned, seems to have been returned to furthering more art, including angling, which he seriously regarded as an art form, not a science. There are so many things that rang bells with my own early life that I began to wonder whether or not I had betrayed the artistic skills which run in my own family when I became a scientist. There are little hiccups in his philosophy, though, which returned me to sanity. He recalls the appearance of material called Bakelite and the reels made of it: he found them quite repellent. I had one as a boy, have two now, and I think they are beautiful. He was, naturally, comparing them with wood and with beautifully turned metal reels; I compare them with today’s rather grand reels, and reels with wobbly spindles. Is our aesthetic appreciation of art a time-controlled thing? Does it change as the fabric of society changes? Or is Venables correct when he claims that draughtsmanship, and drawing, are quite crucial and underline all good art, and that C When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission, which supports our community.

|

Welcome!Log into your account