| MARK WINTLE |

Mark Wintle, an angler for thirty-five years, is on a quest to discover and bring to you the magic of fishing. Previously heavily involved with match fishing he now fishes for the sheer fun of it. With an open and enquiring mind, each week Mark will bring to you articles on fishing different rivers, different methods and what makes rivers, and occasionally stillwaters, tick. Add to this a mixed bag of articles on catching big fish; tackle design, angling politics and a few surprises. Are you stuck in a rut fishing the same swim every week? Do you dare to try something different and see a whole new world of angling open up? Yes? Then read Mark Wintle’s regular column. |

WALKER WAS WRONG (OCCASIONALLY)

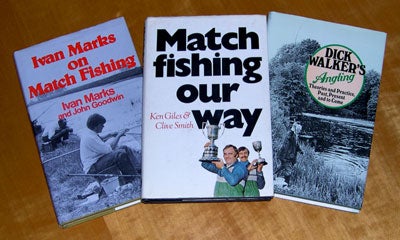

I can hear Ron choking on his cornflakes. Dick Walker wrong? Never! Don’t get me wrong, Dick Walker was right about far more than he ever was wrong about, but just occasionally even he couldn’t see the wood for the trees. Of course, now and again he was put up to it by mischievous editors who fancied creating a stir, but I’m looking for the blind spots. I certainly haven’t read all of his prodigious output. From the fifties to the eighties his articles popped up everywhere. I would not even like to hazard a guess at the total but over two thousand, possibly three thousand or more; we’re talking about millions of words. The Angling Times column ran for thirty years, and I’ve uncovered articles in Fishing, Angling, Trout and Salmon, Coarse Fisherman, Anglers World, Fisherman, Creel…. So it’s hardly surprising that now and again he had a blind spot. I think that as anglers we all have them to some extent. If we’re lucky someone will gently point out the error of our ways, and we learn from the experience but there are always a few sticking points. Many times the converse was true. Walker was often so far ahead of the rest of the pack that when he did discover something new others attempted to discredit him because they were unable to understand or accept his new thinking. For instance, when carbon fibre was developed in the Aircraft Research establishment at Farnborough, Walker was one of the first to see its potential for fishing rods. At that time, although fibreglass had been around for many years, it had yet to reach its full potential, and early attempts to use carbon fibre weren’t always successful. It took many years and much improvement in resin technology and mandrel design to get the best from carbon (and we haven’t necessarily reached the end of the road yet) before it became the widely accepted material that it is now. But as these two examples show, now and again even Dick walker struggled to make sense of the complexities of angling. Fishing fine – Walker versus Clive Smith Around 1973, Clive Smith had a regular match fishing column in Angling Times. In those far off days standard match tackle was 1.7lb mainline and 1.1lb hook lengths (Bayer Perlon of course). This was fine for dace, roach and skimmers but on some waters like parts of the Severn, and improving Trent and some other waters, chub were playing an increasing role in catches. The development of waggler methods and the use of casters put far bank chub swims within reach on waters like the upper Thames and Warwickshire Avon. Suddenly, match anglers were getting stuck into far more chub (and barbel on the Severn). What they weren’t always doing was landing them. Reports of ‘Joe Bloggs’ hooking ten chub and landing three became commonplace. Dick Walker was far from impressed. In a typically blunt attack on match anglers, he advocated the sort of tackle that was standard on his water on the upper Ouse; 6lb line, a substantial hook and a rod to match – a Mark IV Avon. Far better, he argued to hook three fish and land them than to hook ten and lose the lot.

Clive Smith countered valiantly. He told Walker to stick to what he knew and let match anglers work it out for themselves. All sorts of ridiculous arguments ensued. Balanced tackle was the answer from one quarter; why even a 40lb carp could be subdued on 1lb line if the tackle was balanced. “Bullocks” said Walker (I think that’s what he said). The real problem was that neither Smith nor Walker was really seeing the others’ point of view. Walker couldn’t see that the tackle and tactics he advocated would fail to raise a bite in the conditions facing match anglers. Smith had little experience of the jungle warfare that Walker was prepared to wage on chub. In the event, a new match tactic rendered the arguments pointless. The swimfeeder revolutionised chub and barbel match fishing, and suddenly it was possible for match anglers to use much stronger tackle and catch fish. Since then the tackle we all use has come on in leaps and bounds, and it is possible to use far stronger tackle whilst retaining the finesse thanks to co-polymer and fluorocarbon lines, better hooks and much better rods. Shotting patterns A similar argument ensued when it came to shotting patterns for floats. Again, Walker took the opposite view to the match anglers. As far as he was concerned floats should be simple, indeed bird quills ought to suffice for 90% of floatfishing, and as for shotting patterns then bunch the lot in one place. He saw little need for dropper shot or fancy patterns. Now, at about that time (the early seventies) Geoffrey Bucknall was spending a lot of time in France trying to understand how French match anglers went about their fishing. He then wrote articles explaining what they did. They (the French) had developed all sorts of interesting shotting patterns; apart from the ubiquitous bulk and dropper, there were the familiar shirt-button and also variations on a theme known as logarithmic. This is where the shot is grouped in bunches and the size of the bunch increases or decreases as you get nearer the hook.

Many British match anglers understood and developed their own variations of these patterns. The tapered shirt-button style formed one of the basic patterns for stick float fishing. But many other intricate patterns had been developed by top anglers like the legendary Ivan Marks for specific purposes. He understood where a shotting pattern could be used to achieve a specific bait presentation, beat adverse wind and current conditions, or defeat the attentions of nuisance fish like bleak. Dick Walker was having none of it. But again it was a difference in the type of fishing experienced that clouded his judgement. Ivan was fishing the big match waters like the Welland, Nene, Witham, Severn and Trent. The float fishing demands were far different to those of the upper Ouse, Beane and Ivel. Walker had little need to cast floats long distances nor fish for chub with waggler floats (a style that he particularly detested). Again, the specialisation developed by the top match anglers could not be faulted, and Walker could not see that such methods were essential. Where Walker did have a point, and this remains true today, is that for the average angler, fishing quietly without the pressures of match fishing, can use simple float methods and shotting patterns, something worth considering today. Those two stories are much condensed versions of events that took place thirty years ago. I could fill a book of examples where he was right but it does show that even our brightest thinkers can’t be right all the time. The modern slant on this is where methods are developed by thinking anglers fishing for carp, barbel, pike, or match fishing, and before you know it that method is being slavishly adopted widely regardless of its suitability. When someone challenges such unthinking orthodoxy they face fierce criticism. Like many others I am eagerly awaiting Barrie Rickard’s biography of Dick Walker. He certainly was a complex man, and I know that not all of the story can be told. He was no demi-god but remains an inspiration and influence on much of our fishing today. |