This is a new series for Fishing Magic and the concept sounds a good one to us. Dave Coster is a hugely respected guy on the match scene, whereas specialist angler John Bailey has caught a good few big fish in his lifetime too. DC tends to be more of a box man, and JB admits to not even owning a chair. What we hope is that the differing methods employed by these two experts will dovetail and shed new light on all the topics the pair decide to cover. We’d like to think that the information the pair give us will provide a pretty sound base for you to build on… whatever the subject. As you see, they are kicking off with Small River Chub but coming up are their ways with Bread and with Wagglers. What we hope here is that we get YOUR requests and hear what YOU would like to see the pair discuss.

Dave Coster – My Way with Small River Chub

SMALL RIVER THINKING

I’ve always been fascinated by chub, particularly those that inhabit small rivers. Very often you can walk for miles and not see any signs of these fish, but they will be there. In my experience there are two main ways of finding small river chub: the roving or static approaches. Having fished with John Bailey, I know he loves keeping mobile on this type of water. I once followed him and watched, fascinated, as he worked his way downstream, exploring all sorts of interesting features. He gave some areas longer than others, relying on his watercraft to let him know when to move on. Me, I could only go so far, lumbering along behind, laden down with my usual mountain of gear. John travelled light with just one rod, plus some bits and pieces. He was as fleet-footed as a footballer about to score a goal. I totally get what this roving approach is all about, but I also know that carefully selecting a swim and sticking with it for the whole session can be equally effective.

TORPEDO CHUB

Chub can be as spooky as hell, not surprising because they have to be in order to survive otters, mink and cormorants. Medium-sized river chub are like torpedoes in the way they home in on any cover or snags a swim holds, performing that inbuilt trick of transferring your hook into something immovable. A favourite way these fish have of escaping is to dive under the nearside bank, where they know every sunken branch, or tangle of underwater roots. They are streetwise, which is why most of the time I like to use a 13-foot float rod, rather than anything shorter, even on very narrow runs. I’ve often thought about using less long pellet waggler-style rods for this type of fishing. Some models have suitable actions for light line and big fish applications, but when long trotting I prefer the extra leverage a longer, more traditional float rod provides. Also, if you need to scale down your tackle to winkle bites out of nothing, a long rod helps to prevent getting broken up by big fish.

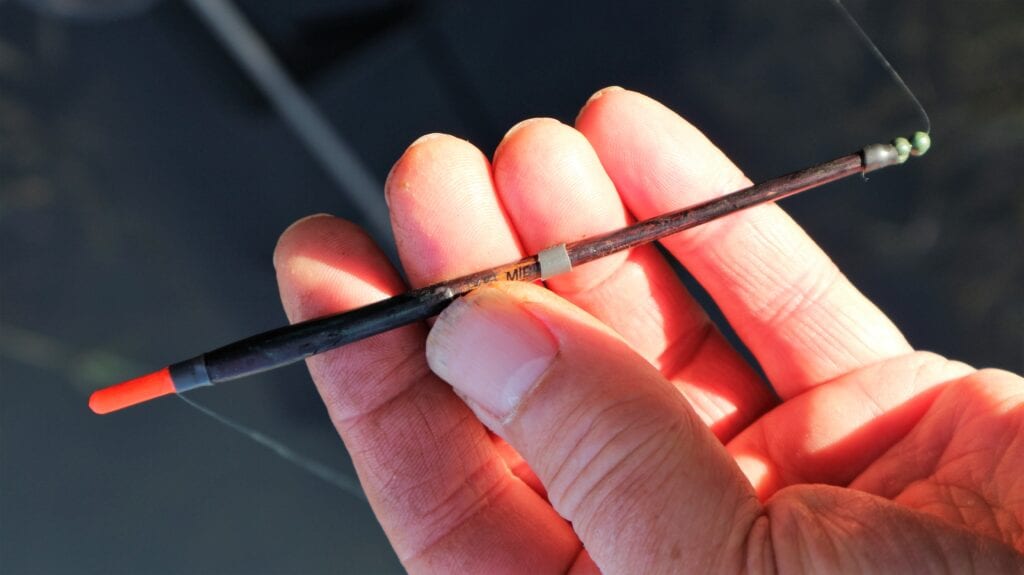

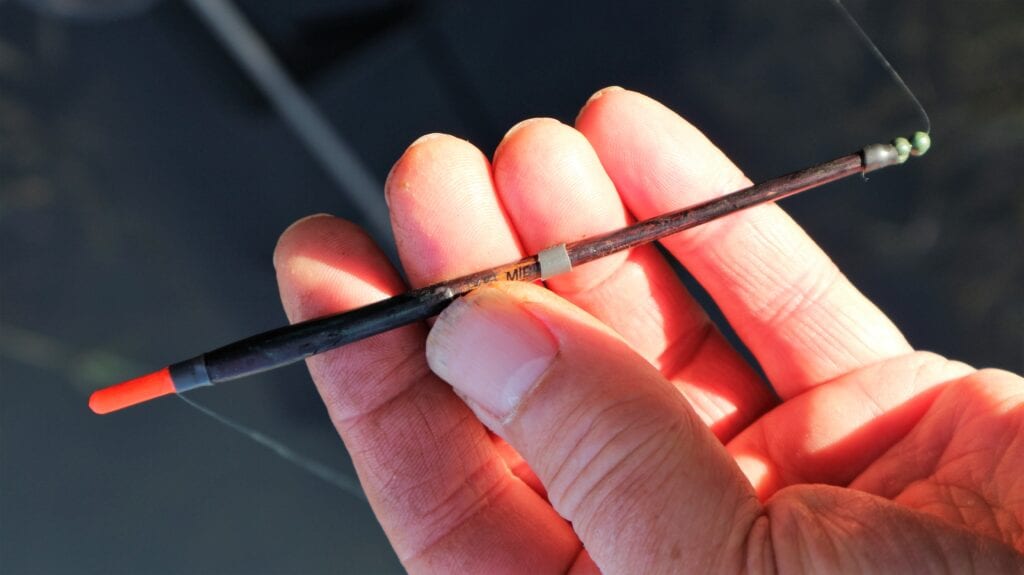

MINI STICKS

I have spent a lot of time getting the floats I use for small river fishing right. Normal stick floats are too long and carry too much shot, plus they are hard to see when trotting long distances. I have sorted this out, by trimming down the bodies on some of the smaller floats in my collection, so they carry less weight, also replacing the balsa tips with hollow plastic ones. The latter are translucent and much easier to see when long trotting. This makes a huge difference, allowing me to keep track of my floats much further downstream, especially when they are travelling into dark water. As a good example, if you ever try trotting a conventional stick float under a bridge it becomes almost impossible to see. This is because the bright tip colour will be painted over a white undercoat, with balsa underneath. Low light levels can’t penetrate, so the tip disappears from sight. Not so with hollow plastic, providing the fluorescent tip colour is painted directly onto it, with no undercoat.

SIMPLE RIGGING

Many of the small river swims I fish are very shallow, often less than 2 feet deep. With such minimal water to play with I don’t want shot spread all over the place. With most of my mini sticks I fix a couple of number four shot underneath the stem, leaving just enough room for two spread out number 8s below. Having such light shotting down the rig helps to prevent it constantly dragging under, particularly if there is any bottom weed. Other important factors are hook size and line diameter. My early match fishing days taught me how to fool chub by using small hooks and fine lines. It was extremely hairy playing lively chub on super-fine gear, but I was getting bites when those around me were dry netting. That factor leads me to always check the diameter of my rig lines, making sure they are accurate. I don’t want to think I’m using a two or three-pound hook length, when in reality it is much thicker and deceptively stronger, failing to gain me those vital bites.

SWIM CHOICE

It might be okay, with the roving approach, to dive in with a bait right on the nose of where you expect any chub to be lurking, because you can catch one or two and then move on. But I don’t want to catch a couple of quick fish and then sit bite-less for the rest of the day. My plan is to carefully feed fish up to me, picking a long straight glide above any fish-holding features. This way, if I can feed the fish up to me, I will catch a lot more. This is due to chub having one big weakness. If you can get them competing for loose feed, they tend to lose all caution. This is another match fishing trick I used to employ on wide canalised rivers, feeding far bank chub haunts for two or three hours before casting over there, messing around on the pole first, catching small fish closer in. Other competitors would go straight over and nick a quick brace, but that would be their lot. By the time I went across, just about every chub in the stretch would be in front of me. You can imagine what happened next.

WAITING GAME

It can take several hours to make things happen when trotting light float tackle down a long, shallow glide. However, there are little tricks you can try to help pull fish into your swim faster. A good one is to not pick up your rod to begin with, simply feeding a few casters or maggots every few minutes for at least half an hour. In my case, I like to feed a mixture of hemp and casters, especially in fast-flowing water. This way, I know I will gradually build up a good bed of fish-attracting seeds on the bottom, while the casters will tend to waft around all over the place and continue to roll a long way down the run. During initial feeding I catapult the odd pouchful of casters well down my swim, to try and pull fish up even quicker. I prefer casters because they don’t attract quite so many nuisance fish like minnows, bleak and small dace. They don’t stand out too brightly when they finally come to rest either. Swans on my local river upend if they spot anything on the bottom when passing through.

SWIM BUILDING

Even with my hemp and caster approach, minnows and other small fish can be a nuisance, but then again, the activity can help to pull chub into the swim. When working float tackle through a long glide, it can take several hours before any big fish arrive, but I am willing to take this gamble. If they do turn up, a hectic final hour might follow, catching wise old chub, which I don’t think have ever been hooked before. Working a swim hard before it comes to life properly can be rewarding, too, honing up your tackle control and remembering the different ways of making a hook bait behave. Top stick float anglers I have had the pleasure of fishing with in the past, have different ideas about how a float should be presented. Some trot with the flow and don’t mess about with it too much, while others liked to slow the flow of line off the reel’s spool, either by feathering it, or hand-feeding it off. I like to try all these things. Some work better than others on different occasions.

SWITCHING ON

The first time I encountered the big Upper Witham chub I had heard inhabit my local stretches, I was in for a shock. I had been running a small stick float down my swim for several hours, only catching minnows, tiny dace and small grayling. Then something changed. It was like that eerie stillness you get just before a storm. The tiny orange speck that was the tip of my stick float was suddenly rocked as something big and unseen moved under the surface. The float vanished and my rod bent into a surging force that was moving downstream at a rate of knots. I was worried that my fragile hook length was not going to cope, but it’s amazing how much punishment a forgiving-action float rod can absorb. Somehow, I managed to turn the fish and start gaining line. As it came upstream, head-shaking thumps were transmitted down my rod as the fish tried to shed the hook. I kept constant pressure on and everything held. An angry monster of a chub eventually went in my landing net, thrashing about like a demon. Several more followed, in an action-packed hour I will never forget.

RESERVE METHOD

Of course, not every session turns out quite as successful as the one I have just described. Going back to try for similar success wasn’t easy because small rivers can be temperamental. They need to be right, fining down after heavy rain, with some colour remaining, otherwise it can often be hard graft. Another thing I’ve learnt is that hefty chub won’t always dart about for small baits, cleverly moving into the swim without you knowing, quietly picking up inert freebies laying on the bottom. That’s why it’s worth setting up a light bomb rig as backup. If bites have dried up after several hours, or have not been happening in the first place with float tackle, it’s a good idea to try working a light bomb down the swim, covering a few yards at a time. Very often a still bait on a short 12-inch hook length will bring a savage take straight away. Double caster is good, as are double red maggots.

ANOTHER ROUTE

There is yet another way of finding small river chub when sticking with one swim all day and that’s to target other species first, particularly dace. I love a session on these fish, which often feed all day, even in the depths of winter. You need to be fast to connect with the lightning-fast bites, and keep changing hook baits, because if you get a crushed caster or stretched maggot, dace will be almost impossible to connect with. Occasionally, small chub turn up amongst a shoal, but the thing to look out for is when bites suddenly dry up after a hectic few hours. This normally means something big has moved in. You might be unlucky and discover it’s a pike, but on many occasions it can be chub spooking the shoal. The chub eventually find some of the loose feed that’s getting through the smaller fish. This pulls them up into all the activity, eventually pushing everything else out.

HOW BIG?

The first time I targeted big chub on my local small river I had a new camera with me, which I hadn’t mastered properly, plus I forgot to take my scales along. To be honest, I wasn’t expecting anything great to happen because I had virtually zero information, apart from word of mouth that the stretch held good fish. I had walked the river a few days previously, noting likely looking swims. Of course, the best looking one was the longest walk, three muddy fields between the nearest access points. I went for it, fished the peg for several hours and caught virtually nothing, before somebody must have flicked a switch. The swim in question was on a long straight, 30 metres above a bend with some nice-looking tree cover. That’s where I expected any chub to live and after feeding small amounts of hemp and casters every cast, the fish eventually moved upstream to me and I caught several of them when they went into an unusual feeding frenzy. What would the largest ones have weighed? I haven’t a clue, but against my seat box you can see they were pretty damn big!

JB’s Way with Small River Chub

First up, I’d like to say that a small river for me means anything from the upper/middle Wye downwards. That would include the East Anglian rivers, many of the Wessex rivers, the Ouse, and many of the Yorkshire rivers, but exclude the Trent, Thames and Severn. So, I guess most chub venues are covered by what DC and I are writing about this time round.

Second, I’d agree with every word DC writes, especially as my favourite fishing method on earth is long trotting a medium-paced run around 4 feet deep. I love to settle into a swim which I know has fish – especially chub – and build it up the way DC describes. Heaven.

Third, when this is not on the cards, as DC says, I love to roam for my chub and that approach forms the basis of what I am describing today. Dave paints a very gung-ho picture of me… which I like! I always insist fishing is a sport, NOT a pastime or hobby, and I think the athleticism employed by roving anglers backs this assertion up. You try walking miles on a steaming day through nettles, brambles and bogs and then tell me this is like stamp collecting!

THE CHANGING CHUB SCENE

Back in the Eighties, I co-authored a specialist book on chub fishing with Roger Miller, and I guess less than 50% is relevant today. Most of what we knew about chub fishing was written before otters and cormorants had become the plague they are today. DC mentions the problems predators pose, but I would like to take this further. Because of these new dangers, chub have changed their lifestyles over the past 30 to 40 years. They are far more nomadic. They have become wary of slow, deeper water where they are vulnerable to attack. They look more to shallows, where they feel safer from otters, and sanctuary within marginal weed growth has become ever more attractive. Whereas Miller and I wrote enthusiastically about chub on surface baits, today I find it rare that chub will come up for, say, crust.

In fact, I’d say that there are times in the summer when the river is low and clear and the sun is up, when chub today are virtually IMPOSSIBLE to catch at all, so wary have they become. Your only chance is to place a big impact bait close by them without scaring the hell out of them. A size 6 with double lobworm. A dead gudgeon. If the Environment Agency would allow it, a dead signal crayfish would be perfect. I have put a single grain of sweet corn in front of a chub on days like this and seen them torpedo off downriver. Normal approaches very often will just not do!

SWIMS FOR THE ROVING ANGLER

As DC says, watercraft is all, or nearly so. I have said that I look to the quicker, gravel shallows where there is oxygen, plenty of invertebrate life and, yes, juicy crayfish. Clean gravel and sand indicates fish are used to feeding over it, so that is always a clue. Over the years, the traditional “raft” swim has become less of a magnet to chub. Today, they prefer those banks where there are extensive blankets of floating weed, like watercress. Chub will spend long periods of the day tucked in there, safe and sound, coming out every hour or so to have a shufti around and see what’s happening! Yes, the “old” swims will hold fish. You will find them on deeper, slower bends and under rafts, but don’t expect them to live there for long periods, like they used to. One whiff of predator and they are gone, sometimes miles. I’ll tell you a story.

I had dropped Ray on a long glide to trot with maggots. I had then driven Adrian over two miles downriver to deeper water to fish boilies and pellets. At 10.05 am Adrian landed a chub of 6.02 but as we unhooked it, it spewed out fresh, wriggling red maggots! At around 9.30am Ray reported hooking and pulling out of a big fish. There were no other anglers on the stretch and the only conclusion is that the lost chub had spooked and fled two miles plus in half an hour before stopping in front of Adrian and making the second mistake of the morning. That is the type of fish we are talking about here. Fish that get the hell out at the first whiff of danger.

THE ROVING BASICS

Let’s assume there is a good stretch of river available with not too many anglers on it. We are looking any time June ’till November, or even in the winter if levels are not too high. In a perfect world, I will walk between 3 and 5 miles downriver, dropping bait into likely swims as I go. I will then fish my way back, investigating all the swims I have baited. I might well cover 8 miles in a day and fish upwards of 20 or 30 swims. If there is a bit of colour, I’d expect bites or fish in at least half of them.

Bait? 10mm pellets. 12mm boilies. Cheese paste dollops. Corn. Bread, either flake or mash. Scraps of luncheon meat. Chopped fish bits. I won’t put much into each spot, perhaps just half a handful, or in the case of boilies perhaps four or five, no more.

Gear? Polaroids are number one. Breathable chest waders are number two. These allow you to walk comfortably long distances in the heat and to get in if required. They also give protection from wasps, ants, nettles, brambles and every nasty out there. A SOFT tip rod. I like my 12ft ancient North Western which has a blank floppy as rhubarb. 4 or 5 pound line. A centre pin generally. A net with a metal rim, not a drawstring type. There are many occasions when you need to dig a chub out of thick weed and drawstrings collapse on you. Bait in a bucket. A pocket with spare hooks and shot. That’s it. No bags, chairs or boxes. You’re hunting! Go get them!

THE ROVING APPROACH

A shadow can kill you. Vibration can kill you. Most of all, a bait going in with a splash will kill you stone dead. This is no place for leads or feeders, and the most you’ll see me use outside flood conditions is one SSG or, more commonly, two AAAs or three or four BBs. Very often there will be no weight on my line whatsoever and if I do use AAAs or BBs, I’ll space them up the line a foot apart so that they do not break the surface with a splash.

I’ll never put a bait on a chub’s nose but always upstream so it drifts with the flow down towards it. Consider how strong the current is and place the bait accordingly. I prefer not to see the actual fish before casting. I’ll have made a mental note where to put the bait beforehand, when I have put the loose feed in. Remember, if you look to see the fish, the chances are the fish will clock you first, time after time. Don’t risk it. Chances are, all you’ll spot anyway is a disappearing tail.

Trust your watercraft. Make the first cast perfect, and put it exactly where you want it. No false casting. No casting into weeds or branches. Get it right from the get-go. Prop the rod in the reeds and wait. Don’t peer over the foliage, or shuffle, or get fidgety. Give it at least ten minutes on that cast before moving on. Don’t always expect a crash-bang bite. A wary chub will look at a bait again and again if it is unsure of things. Sometimes, you’ll get flicks on the tip as a bait is nosed, picked up and generally investigated. This is cat-and-mouse stuff. This is you and a chub at ten paces, and make a single error and you can forget it. There are times I know I have blown it before even casting in. Perhaps my approach was noisy or perhaps I disturbed a coot or moorhen on my way in. At least by roving you’ll have second bites of the cherry as you move onto your next swim.

If/when you hook a chub on a small tight swim, be its master. Do not let it dictate matters, and be especially careful when it heads for the cover of either the far bank or the snags at your feet. Really pile on pressure to keep it out – I’d rather lose a chub by being bold than being a bed-wetter! IF the chub gets into the weed mat, that is where your metal rim comes in. At least you can dig around and push through the obstructions ’till you get to what is often a tethered fish.

In short, this is about as exhilarating and exhausting as fishing gets in my view. If you don’t get back to the car shattered mentally and physically, then you probably haven’t been doing it right. There are some colossal chub out there. In my view, on smaller rivers, this is the way to get them!!