Alongside riding and hunting and many other country sports, angling has a long history of art associated with it that today shows little sign of diminishing. Indeed, even in this modern age of digital wizardry many angling authors still prefer paintings to photographs to adorn the covers of their books. Photography is fantastic for catching and documenting occasions, scenes and moods but painting and drawing has the capacity to go beyond this by creating images out of the imagination that are uninhibited by needing to have a camera ready in exactly the right place at the right time. The camera sees what the camera sees, you can tamper with it here and there using technical trickery and Photoshop wizardry but the artist’s brushes are not remotely restricted by what is and can create whatever subjects, moods and emotions are required, sometimes even conjuring up an entire story in single image!

Looking back to my childhood days it was Bernard Venables’ comic strip artwork in his book ‘Mr Crabtree Goes Fishing’ that first moved me to want to go fishing at every opportunity. While comic strips were frowned upon by our teachers at school, we loved them all the same. The act of marrying the text together with the image created something immediately accessible and entertaining. Lowbrow as comic strips may have been, Venables fired my imagination and ignited a passion for angling in me that has endured ever since. I doubt that written words alone could have achieved this and, it is a fact that while I was reading everything about fishing I could get my hands on in my early years, I can barely remember a single word from any of those ‘how to do it’ fishing books (though I obviously retained the gist of it), but I can remember many of the Crabtree comic strip frames in perfect detail, both the fish that were caught and the fisheries that were visited. That is the measure of just how good Venables was, and is a perfect example of just how effective an artist’s pens and brushes can be.

Venables’ drawings gave fish life and beauty and made the prospect of catching them incredibly exciting. In creating scenes in which his creations, Mr Crabtree and Peter, fished famous fisheries such as the Hampshire Avon and Norfolk Broads, he also sowed seeds of awareness in me of the geographical layout of the English countryside. Through Venables’ books I could instantly pinpoint the location of Norfolk Broads, the Witham and the Great Ouse on the map. I also completely understood why the Hampshire Avon was so very special, even if I had never been there – and that was something even my teachers didn’t know! When in my adult years, I eventually got to fish some of these places myself it was like coming home to long lost friends.

Venables’ drawings gave fish life and beauty and made the prospect of catching them incredibly exciting. In creating scenes in which his creations, Mr Crabtree and Peter, fished famous fisheries such as the Hampshire Avon and Norfolk Broads, he also sowed seeds of awareness in me of the geographical layout of the English countryside. Through Venables’ books I could instantly pinpoint the location of Norfolk Broads, the Witham and the Great Ouse on the map. I also completely understood why the Hampshire Avon was so very special, even if I had never been there – and that was something even my teachers didn’t know! When in my adult years, I eventually got to fish some of these places myself it was like coming home to long lost friends.

Unfortunately fishing was not strongly encouraged, ether at home or in school. “Fishing will never earn you a living” said my father and my teachers! And, they were not wrong there, but it did put me in touch with many other aspects of life that have enriched and nourished my own life in so many ways. Around angling I formed friendships, gained an appreciation of my environment and even learned to spread my wings as the need to fish new waters took me ever further from home. Having been hooked by the artwork of Venables, it was only a matter of time before I started to discover other angling artists. The illustrations by Reg Cooke in Richard Walker’s book ‘No Need To Lie’ were arguably as important as Walker’s text itself. Together Walker and Cooke inspired me into taking my own first tentative steps towards trying to catch some specimen fish so big that I also would have no need to lie!

David Carl Forbes delicate and detailed line drawings in his book ‘Small Stream Fishing’ were another inspiration that got me wishing I could draw like that. That revered writer of countryside pursuits, BB, was another illustrator at work during my childhood and youth. While he liked to write under the pseudonyms of BB and Michael Traherne, he published his artwork under his real name, Denys Watkins Pitchford. I cannot say that BB’s artwork had the same impact on me as Venables and Cooke, but his black and white scraper board drawings in particular, were objects of beauty that perfectly caught the bucolic charm of angling as it was before today’s ultra-cult modernity kicked in.

As for my own artistic endeavours, apparently I always had a flare for drawing. The sleeve notes of the first book I ever Illustrated (a children’s book called ‘Tim, Willie And The Wurgles’ by Alan Wakeman, published in 1976) said that Chris Turnbull first learned to draw by smearing mashed potato and gravy in his highchair, and this wasn’t so far from the truth. Various disabilities I had been born with had put me out of action until I was 4 years old, so while my contemporaries were toddling around making mischief, I apparently spent much of my time trying to make scribbling look like something recognisable. Long periods of my primary school years were spent in hospital dwindling away the weeks, drawing pictures from my imagination. When I finally did return to school, I had drifted so far behind my classmates that my teacher put me at the back of the class to scratch away quietly with my pencil and paper. Classes were large back then and teachers had little time for a child’s individual needs. Luckily my Mother stepped in and got me into a new school where they could put my education back on track, but by then the damage had been done… I had become a budding artist.

As for my own artistic endeavours, apparently I always had a flare for drawing. The sleeve notes of the first book I ever Illustrated (a children’s book called ‘Tim, Willie And The Wurgles’ by Alan Wakeman, published in 1976) said that Chris Turnbull first learned to draw by smearing mashed potato and gravy in his highchair, and this wasn’t so far from the truth. Various disabilities I had been born with had put me out of action until I was 4 years old, so while my contemporaries were toddling around making mischief, I apparently spent much of my time trying to make scribbling look like something recognisable. Long periods of my primary school years were spent in hospital dwindling away the weeks, drawing pictures from my imagination. When I finally did return to school, I had drifted so far behind my classmates that my teacher put me at the back of the class to scratch away quietly with my pencil and paper. Classes were large back then and teachers had little time for a child’s individual needs. Luckily my Mother stepped in and got me into a new school where they could put my education back on track, but by then the damage had been done… I had become a budding artist.

It was hardly surprising that once I took up fishing and found mentors like Venables and Cooke to aspire to, drawing fish would become one of my favourite subjects. After eventually leaving secondary school and going on to the Medway College of Art other subjects inevitably took precedence. I do remember painting one fish there, however, in a still-life drawing class taken by a highly eccentric tutor called Mr Spike. Old ‘Spike’ was notorious for chopping off the bottom half of student’s ties so that they couldn’t dangle in the paint. He also had a knack of being able to come up with whatever subject matter any student wanted to paint. One day after he had presented us with yet another pile of old junk to portray, I expressed a fancy that I wanted to paint a fish. Ten minutes later he returned from the fish mongers with a glistening rainbow trout that presumably he later ate for tea. The following week I thought I’d push him further to see just how obliging he could be, so I told him I wanted to paint a rowing boat…. and would you believe he had one in the back of his van?!!!

I left art school in 1970 but looking back at the early 70s, my impression is that these had become somewhat leaner years for angling art than the previous decade. Keith Linsell was probably illustrating more fishing books than anyone at the time but for me, his work didn’t conjure up the same magic as Venables and Cooke, despite his technique being superior in many ways. As for my own efforts, it wasn’t until the end of the 70s that I started getting the odd drawing published in ‘Coarse Angler’ and ‘Coarse Fisherman’ magazines.

As the early 80s dawned angling publishing in the UK was still producing little of artistic merit to get excited about. Black and white snapshot photography was about as good as it got in the fishing mags, with a colour photograph stuck on the cover. Fishing books were little better, but at least some of the writing was good. Coarse fishing artwork was virtually non-existent, though the game fishing fraternity was better provided for, with the paintings of Robin Armstrong being prominent as I recall.

As the early 80s dawned angling publishing in the UK was still producing little of artistic merit to get excited about. Black and white snapshot photography was about as good as it got in the fishing mags, with a colour photograph stuck on the cover. Fishing books were little better, but at least some of the writing was good. Coarse fishing artwork was virtually non-existent, though the game fishing fraternity was better provided for, with the paintings of Robin Armstrong being prominent as I recall.

In 1980 I moved to Norfolk, drawn by the quality of its fishing at the time. Back then the Norfolk specimen scene was like a ‘who’s who’ in the angling world, with the writings of various Norfolk anglers dominating the magazines. It didn’t take long before I started making acquaintance with some of the county’s angling stars, ether on the river bank or, more likely, gossiping in hushed tones at the far end of John Wilson’s Tackle Den. Up until then my efforts as an illustrator had mostly revolved around doing fantasy images, including the odd LP record covers and the occasional children’s book, but I was increasingly keen to find some openings in which to publish some paintings of fish. After cold-calling John Bailey by phone, I arranged to meet up with him at his home in Costessey Mill house to see if showing him my artwork might identify any possibilities?

In 1983 a book entitled ‘The New Complete Angler’ was published by Stephen Downs. In itself this was not a remarkable book, except that being illustrated throughout by the paintings of an artist called Martin Knowelden, it did prove that a fishing book could be a thing of beauty. By the time this book was published, John Bailey and I had already started collaborating on creating his first book ‘In Visible Waters. Published by Crowood Press in 1984, this book contained no photographs but was illustrated by my artwork throughout with a block of water colour paintings contained in the middle and numerous pen and ink line drawings scattered throughout. Like all books in the Crowood stable, this one earned only a pittance; nevertheless it was well received and started to establish me as an angling artist. Today it is classed as an angling classic with good conditioned 1st edition copies going for around £40. Now, when I look at its colour plates, I do so with some disappointment as my painting has come a long way since then, but everyone has to start somewhere!

Throughout the 1980’s just about anybody that had ever wielded a fishing rod seemed to be writing a book, with John becoming the most prolific author of that era. Collaborating with John for several more years, I did the artwork for all of his books and, in the bargain, become the most prolific angling book illustrator around. Before the decade was through I’d also starting to write, edit and illustrate the first of a number of fishing books of my own. Created in the last months of the 80s and chronicling events at a number of the top specimen waters of that decade, my book ‘Big Fish From Famous Waters’ provided an abundant showpiece for my artwork. Throughout the early 90’s, any author wanting artwork for their new fishing book seemed to be coming to me, with Dave Plummer, Richie McDonald, Graeme Pullen and John Wilson all calling on my services. And then, almost out of the blue the fishing book market totally collapsed. With virtually all the reputable book publishers having seemingly lost interest in producing fishing books, any chance of an author earning any royalties beyond his initial advance of around £1,500 became very unlikely. This was largely due to the budget book clubs whittling down the profit-margins. And of course, at around the same time, the age of the angling videos kicked in, with the result being that fishing books looked like becoming a thing of the past.

For myself I took to working for a wildlife art agency painting a variety of wildlife subjects, though still mostly specialising in fish. Whereas illustrating angling books had previously paid pocket money, this work actually paid the bills. Painting on a full-time basis also had the benefit of allowing me to hone my skills and explore new mediums. Whereas I had previously mostly used Gouache water colours, I’d long felt this medium had been holding me back. Increasingly I turned to using acrylic inks and paints to get the effects I was looking for, building up and overlaying colours in a way that is not possible with water colours. If I have any gripes about this period of working as a jobbing illustrator it was the tedium of having to always work up every last tiny, tedious detail of everything. Then, having worked endless days (and nights), I ended up finding myself with nothing of lasting value to show for it, even if my efforts had earned me a living.

Throughout this period, fishing book publishing had remained largely in the doldrums, although angling prints had started gaining a market, with companies such as ‘Planet Prints’ specialising in reproducing angling artworks. This included several images of my own, though looking at them now, I feel they suffered from having too much detail at the expense of the impact of the overall image. This was the legacy of working as an illustrator. I had always loved the work of the ‘Impressionists’ but, due to commercial restraints, I had never been allowed to indulge myself in their loose brushstroke techniques.

Throughout this period, fishing book publishing had remained largely in the doldrums, although angling prints had started gaining a market, with companies such as ‘Planet Prints’ specialising in reproducing angling artworks. This included several images of my own, though looking at them now, I feel they suffered from having too much detail at the expense of the impact of the overall image. This was the legacy of working as an illustrator. I had always loved the work of the ‘Impressionists’ but, due to commercial restraints, I had never been allowed to indulge myself in their loose brushstroke techniques.

In the 1990s the arrival of the internet and world-wide-web presented opportunities for artists to set up their own websites to promote and market their work. Digital technology turned out to be a double-edged sword for the illustrator though, as while it had opened up opportunities to promote their own work, the publishing world ended up churning out such a profusion of rubbish books featuring second-rate, computer generated artwork for which they paid rock-bottom prices, which had the inevitable consequence of also devaluing an artist’s brushwork.

With the illustration market having now become an increasingly hostile place to work in, I increasingly took to painting private commissions, however, by now, my years as a jobbing illustrator had bled my creativity dry, leaving me feeling like I never wanted to paint again. By taking the opportunity to start painting some larger images as private commissions, however, this allowed me to start developing my painting techniques and begin to create the kind of paintings I wanted to paint. This was like being released from jail and before long my rekindled enthusiasm for painting began blooming into an obsession.

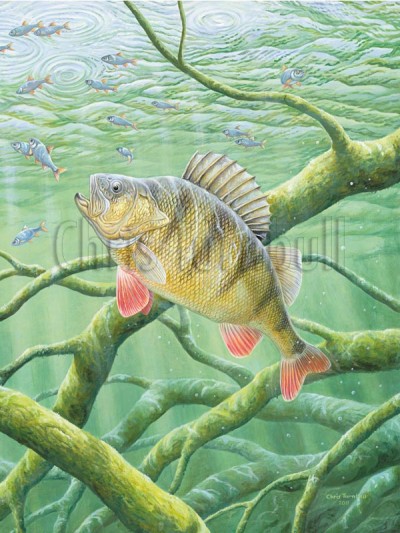

Depicting fish against the backdrop of their aquatic environment is a relatively easy thing to do if you can basically draw okay and fill in colours, but water has density, it moves and it flickers with defused light, Catching anything of this while painting fish that look alive, submerged and swimming, is an impossibly difficult thing to do. Indeed, I now see it as being one of the most difficult challenges an artist can undertake. An artist’s efforts always fall short of creating the images he originally conceived as visual ideas, but painting is not an overnight exploit, it is a lifelong creative process. That popular notion of an artist finally creating his masterpiece is not something he is ever likely to achieve in his own estimation.

Today, the age of self-publishing is with us and a number of writers have taken to publishing and marketing their own books. By doing away with using publishers, distributors, retailers and book clubs, it has become feasible for a large proportion of a book’s cover price to be profit. With only the designer, printer, bookbinder and taxman to pay, even a small print run of 1000 mail-ordered books can be lucrative. While this has resulted in some rather shoddy books being unloaded onto the market, it has also brought about a renaissance of high-quality, full-colour fishing books appearing where the work of the angling artist is once again being valued.

For me this self-publishing industry resulted in a small revival of creating artwork for angling book covers, with both Neville Fickling and the Jason Davis/Eddie Turner collaboration coming to me to provide such artworks. More importantly, self-publishing also opened opportunities for me to publish my artwork. In today’s recession hit UK, the professional artist’s lot is a tenuous one, as few people have excess money to spend on original artwork. Despite this, angling art has seemingly blossomed with David Miller, John Searl and I, amongst others, all making our artwork available as prints. Without doubt the standard of UK angling art has never been higher, as it has to be in such a small, competitive market. Over in the USA angling art is big-business, with artists such as Mark Susinno creating some stunning paintings. If you don’t know his work, I recommend that you Google it up. Certainly he has been an inspiration to me!

For today’s artist, the advent of Giclee fine-art printing has presented the opportunity to produce extremely high-quality, limited-edition prints without making a large financial outlay by providing the means to run off as few as one print to demand. Giclee is the process of making fine art prints from a digital source using inkjet printing. It isn’t cheap but by using the finest light-fast inks and high-quality papers, the Giclee process can reproduce artwork at a quality that is almost indistinguishable from the original paintings.

Over the past few years I have been busily creating a new collection of paintings for reproduction as limited-edition Giclee prints. Meanwhile, working as a graphic designer Stephen Harper has been producing some of the best looking fishing books around…. So when Stephen recently set up a new angling book publishing company and suggested that I put together a new book to publish, the opportunity to create a collection of new paintings to illustrate an autobiographic account of my fishing life was too good to pass by. With the book ‘Reflections’ now in print, I can proudly say the combination of Steve’s design sensitivities alongside my artwork has lifted the bar in creating good looking fishing books.

Hopefully readers will also enjoy the books written content but for me, it has marked a new milestone in my progression as an angling artist. Finally I feel I am coming closer to creating the paintings I always wanted to paint but lacked the opportunities. Today I am as fired up about painting as I ever have been about catching fish. In the article have included a few of my personal favourites from the book and, if you care to take a look, there are many more images on show in my website.