Geoff’s recent article on grayling fishing got me thinking. Grayling are one of our prime winter targets but there is little information in grayling literature about fish location.

In fact a search through my angling library revealed that there is almost no concrete information on location in any grayling book whether it is fly or bait orientated. The Ron Broughton’s book Grayling the Fourth Game fish has one paragraph on location in its one chapter on bait fishing. Reg Righyni devotes several chapters to bait fishing in his seminal work Grayling, but his advice on location is very general. John Roberts’ masterpiece Flyfishing for Grayling has no specific information on location at all! To be fair to these authors, the rationale behind this seems to be that if you’re fly fishing for grayling you are generally fishing for visible fish and if you’re bait fishing you’re carrying out a thorough search of likely grayling locations.

So why the title Cold Water Grayling? Well in my experience as the water cools the behaviour of grayling changes. Although still willing to feed, they become less active, tending to stay in one place and becoming less likely to move far from their lies to take a bait. In this article I’m going to look at two key factors in cold water grayling fishing: locating the fish and presenting a bait to it effectively. What do I mean by cold water? Well when I fished the Calder during the recent cold snap the air temperature was -3C and the water temperature was 1.5C. These are exceptional temperatures for the UK, but on the northern spate rivers winter water temperatures of around 3C are not unusual. These low water temperatures are often combined with gin clear water, making the fishing even more challenging.

|

| Pete Connor trotting for grayling on a freezing day |

Tackle

I’m going to upset a few people here! Whilst I like nothing better than long trotting for grayling with a centre pin reel, in these circumstances (cold, clear water) I would always opt for a fixed spool reel for the increased control it gives me. So why does a fixed spool give more control? The problem with centre pins is that they don’t react quickly to changes in current speed. When the current speeds up the drum has to accelerate and whilst it is doing this the bait rises in the water. When the current slows down the reel will continue to turn at the same speed for some time and the skilled centre pin angler will slow the drum with gentle pressure, but then the current will speed up again…

|

| River Aire grayling caught on a wire stemmed stick float |

In warmer water this doesn’t matter as much as the grayling will be willing to chase its food, but in cold, clear conditions or if the grayling is wary or less inclined to feed then you will miss fish. With a fixed spool you are feeding line by following the float downstream with the rod tip with the line trapped against the rim of the spool with your finger. To feed more line you take your finger off the spool, sweep the rod tip rapidly back upstream, trap the line again with your finger and follow the float down again with the rod tip.

You soon get used to choosing the right moment to sweep the rod tip back and reading the behaviour of the float to slow or speed up the movement of the rod tip. This technique gives superb control over the float on the relatively short trots we will be doing in these conditions.

For this sort of fishing I would always recommend using a match rod rather than a heavier specimen float or trotting specific rod. I use a Shimano TripleX, which is almost perfect, combining a relatively soft tip with enough power in the butt to play good fish in fast water. Float selection and shotting are critical and I will always plump for either a wire stemmed avon or a Drennan loafer shotted in traditional avon style with most of the shot load bulked at about 2/3 depth. For most swims a wire stemmed avon with a shot load of around 4BB is fine, but for heavier flows a 2 or 3 swan loafer will give better control.

|

| A lovely grayling caught in gin clear water |

The key to success is to use a rig which will get the bait down to the bottom as rapidly as possible, but still give reasonable presentation. Because of the clear conditions I’ll be using 0.1mm high strength hook lengths and a size 18 or 20 hook, normally a Drennan Carbon Chub. Grayling have superb eyesight and I’ve found that fishing fine always results in more hooked fish than using heavier tackle – the problem is landing them once hooked! Bait is nearly always maggot, but I do bring worm as a change bait.

One thing I am experimenting with is the use of small coloured beads on the hook length up against the hook to give more visual attraction.

The Crease

Creases, the turbulent boundary between fast and slow water, are classic big fish swims beloved of chub and barbel anglers. Grayling are no different from their coarse cousins and so crease swims are always productive. There’s a classic crease swim on the upper Aire which has produced some big grayling for me. Let’s run a float down it.

The crease is formed by a narrow band of slower water bordering fast gravelly shallows which gradually deepen before dropping into a large pool. Like most anglers I used to give the shallows a few trots before moving down to fish the pool, but one freezing November day I discovered the secret of the crease. The swim has a small alder at its head whose trailing branches prevent a long trot down the crease. I guessed the depth and, holding my rod top high, I lowered the float into the water just below the alder and slightly upstream of my position. By lowering the rod tip I fed line and controlled the speed of the float down the crease. The first time I got the depth slightly wrong so I deepened off slightly and lowered the float in again. This time I could see I’d got the depth right as the float was dipping as the bait tripped the bottom, but the float drifted down the slower water on the inside of the crease. On the third cast I got it right and the float had travelled less than 3 feet before it jabbed under and I hooked a good grayling of just under 2lb. Since then this swim has been one of the most consistent swims for me, nearly always giving me a decent fish and every fish being hooked at the very top of the crease.

1lb 15oz from the River Aire. You can see the crease just over my left shoulder

In my experience this is typical of crease swims with the grayling nearly always holding station in the ‘pocket’ right at the head of the crease. The secret to success in such swims is to vary the speed and the line the float takes as it enters the crease. I always try to position myself just above the pocket and drop the float in slightly upstream of me. By holding the rod upstream I can then let the float run down to the crease under total control, varying the depth, speed and line with each cast until I get a fish or I’m confident that I’ve fully explored the swim. I will only loose-feed maggots in this type of swim if I’m totally confident that they will drop into the pocket at the head of the crease close to the bottom. If in doubt don’t loose feed (unless you really want to catch a trout).

The Scour

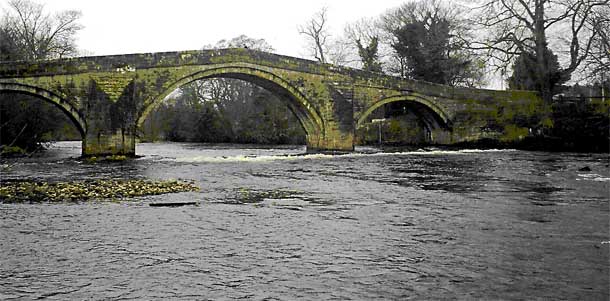

Scour: a lovely northern word! Translation: a depression cut into the river bed by the current. There’s an absolute classic scour on the Wharfe just below the packhorse bridge in Ilkley. The river tumbles down a boulder slope from the old ford and, at one point, has scoured a short, slightly deeper channel in an area of finer gravel. It’s fiendishly difficult to fish as the water upstream is only inches deep and drops rapidly to around 18 inches in the scour itself, but if you get the presentation right you always get a grayling. The secret is to lay the float on the water just upstream of the scour with the bulk shot just into the head of the deeper water. Move the rod tip sharply downstream and the bulk shot will drop into the scour. The total length of trot in this swim is less than 6ft and ten trots will tell you whether or not a grayling is present.

Scour spotting is easy. What you’re looking for are areas of smoother water. Take this swim on the Calder: it’s a fast gravelly run, popply water – perfect for the fly, but about half way down there is an area of smoother water about the size of a small dining table – this is a scour. Again, the challenge is to get the bait into the head of the scour close to the bottom – this is where the grayling will be. The technique is to set the float at or slightly deeper than the depth of the scour, swing the tackle out so that the hook lands a few feet above the smoother water, hold until everything is in line, then move the rod tip smartly downstream. Once the float is fully cocked control its movement down the scour with the rod tip, varying the speed with every cast.

The Bar

A lovely Wharfe grayling caught by trotting along a gravel bar

Unfortunately I’m talking about gravel bars here! But like the office bore on a Friday lunchtime, grayling love to tuck up against a bar. On chalk streams this also applies to bank-side reeds and if the river has scoured out a slightly deeper channel then the chances of finding grayling in residence are even better. This is one feature where I can’t give you an exact point at which you’re likely to find a fish. For some reason grayling appear to come from all points along the length of this type of swim. I’m sure they have their reasons for where they take up station, but to me it isn’t obvious so it pays to explore the whole length of a gravel bar. One thing is certain though – the grayling will be found at the bottom of the slope just where it levels out. Again it pays to experiment with the speed and line until you find fish.

And as a Last Resort…

As I write I’ve just spoken to my mate Pete Connor and he told me an interesting tale of friend of ours, Steve, who fished an Ilkley AA match on the Wharfe last week. This was at the height of the recent cold snap with air temperatures well below freezing and a low, painfully clear river on which all the slower areas had frozen. Steve drew an absolute flyer of a swim, a deep scour with a steep gravel bank to one side of it. After an hour on the float with little to show, Steve switched to a tiny feeder presented just at the bottom of the gravel slope. Steve finished the match with nine grayling (I know, I know….) for just under 13 ½ lb, an average weight of around 1lb 7oz. So in extreme conditions if you’re not catching on the float a small feeder is well worth a go.

Summary

The three swim types described in this article aren’t the only places you’ll find grayling, but they are all places where your chances of contacting a fish are much increased. Even in warmer water, swims like this will be preferred lies or places which grayling will use as a base from which they will venture out to feed. On a strange river swims like this will always be the areas that I’ll try first.

In cold water grayling will always be reluctant to move far to take a bait. This means that traditional long trotting will be less productive as, with this method, bait presentation will always be something of a compromise. In these conditions I’ve always had more success by getting the presentation as near perfect as possible in each area of the swim. This means shorter trots, better float control and continual adjustment of depth and shotting.

|

| Study of a grayling recovering |

All coarse anglers instinctively loose feed when trotting, but in many of the swims I’ve described loose feeding is counter-productive. It’s better to present a single maggot right on a fish’s nose than to spread bait randomly around the swim. Over feeding nearly always encourages nuisance trout to move in and they will often bully grayling out of the swim.

Wire stemmed avons and loafers are relatively inconspicuous and carry shot loads heavy enough to present a bait effectively close to the bottom in heavy flows.

Small hooks and fine hook lengths will always result in more hooked fish than heavier presentations. Using a match rod in these circumstances will result in fewer lost fish than using light gear with a heavy trotting rod.

To get the best presentation on spate rivers you will often have to wade. A fall on a remote stretch of river in these conditions can be fatal. Never fish alone unless you are very experienced and know the river well. A wading staff (trekking poles are a good alternative) is an essential piece of equipment.

Sean Meeghan