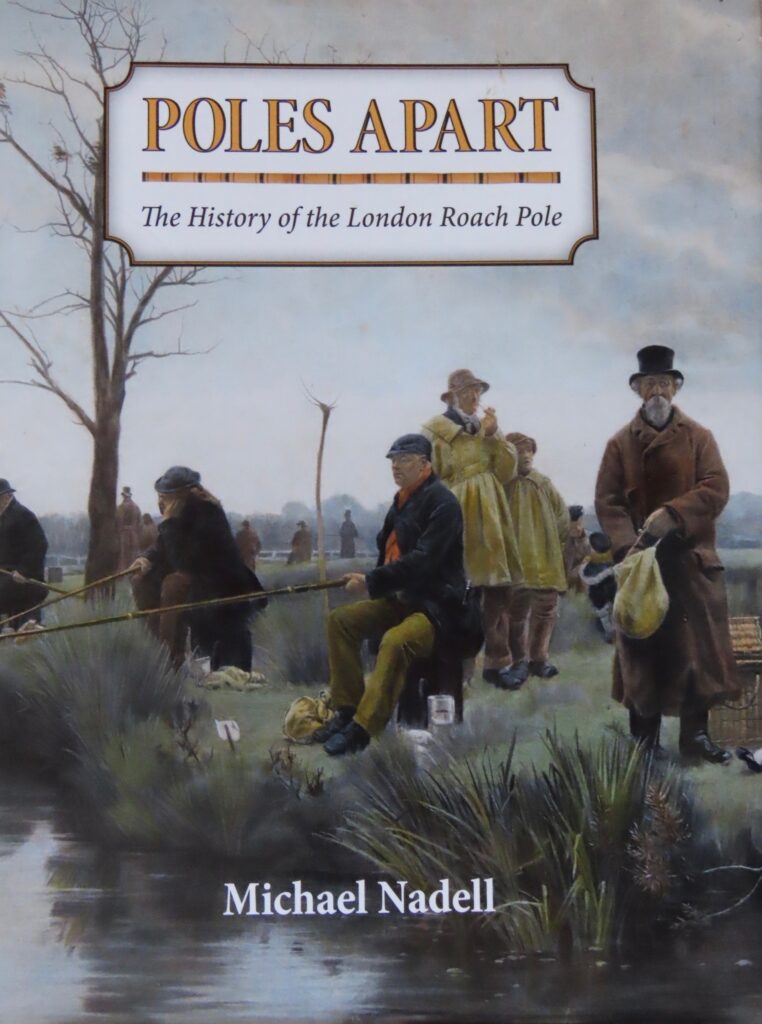

Poles Apart is published by Coch-y-Bonddu Books, and hit our shelves back in 2013. In our view, it remains one of the greatest books for tackle collectors this century for a wide variety of reasons. Above all, absolutely everything anyone would need to know about the London roach pole is written here. This is the result of exhaustive work, and the amount of detail is breathtaking so, if it’s an avid collector you are, then this is a must-have tome. But this is a multi-dimensional work. Poles are the star of the work, if you like, but Michael’s study of them takes us back to the very fabric of London life from the early 1800s.

The fact that Michael is a London man, and was an East End boy, is central to the vibrancy of the whole work. Here is a man who grew up within sight of the Blind Beggar pub and, from being a kid, watched the pole anglers at work on both the Lea and the Thames, yearning to join their ranks. Much pole lore he had to learn for himself, but he writes with love about “the roachers who were tough old boys, braving the severest of conditions. They were also a secretive bunch, rarely disclosing the details of where they caught a good bag of roach or what bait they used.” Michael makes it clear that these were tough men leading hard lives, and the roach pole was key to their enjoyment away from toil and deprivation. Roach as the opiate of the masses? Poles as a matter of life and death? No, they were far more important than that for many, it seems!

Michael reveals himself as a collector, a fisher, an historian, an artist, and a realist. The latter first, then. London in Victorian times was a tough, rough place where poaching was common and bailiffs were treated brutally when they tried to intervene. An angler lagged behind for a pee, and when his mates went back to investigate, they found him robbed and his throat cut. Roach, tench, bream, barbel, all of them were routinely killed, and as often as not left to rot, only adding to the stench of the East End slums and factories. Add in frequent, horrendous river pollutions so, if you are hoping for a Christmas card version of Victorian London, you won’t find it looking along a roach pole.

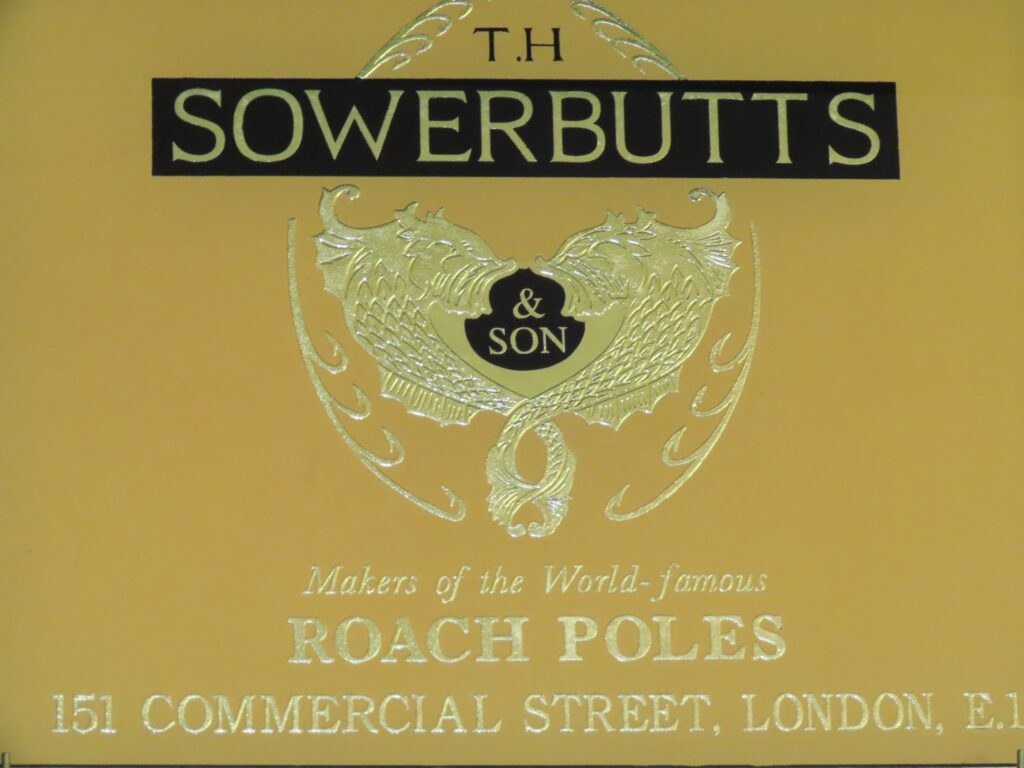

Michael the collector is an easier, drier read. Obviously, the Sowerbutt dynasty is written about in the minutest detail, but a score of makers are also religiously recorded: Evans, Bazin, Carter, Griggs, Martin (Yes, J.W. Martin), Gold, Creeke, Homer and our favourite, the wonderfully named Ebenezer Creed. Their addresses, their dates and the details of their poles are in there, along with their tapers, colours, whippings, ferrules, liners, butt caps, and even prices. Some were made of mahogany, reed, bamboo, split cane, and even whale bone. There were differing lengths for the larger Thames and the smaller Lea, and Michael tells us a thousand things we didn’t know.

Tackle collecting can be divorced from the actual fishing that gear was designed and made for, but Michael is an angler and clearly a good one so there is nothing sterile about Poles Apart. There are simple cracking chapters on how the old maestros fished their poles and the methods that suited them best, from trotting to stret pegging to simple, effective laying-on. Bait droppers. Pole rests. Plummets. Line winders. Boxes, and especially floats and baits. Everything is there to make you the modern pole fisher of renown. We love Michael’s recipes for arrowroot biscuits and special pastes, and sometimes we forget what killing baits caddis grubs, elderberries and pearl barley all are. And, talking of maestros, Michael introduces us to a goodly number here. Robert Slowman and Henry Wix are our favourites. Blimey, could they catch roach! Of Slowman, the great Grenville Fennell writes “it was considered at that period no little honour for anyone to be permitted to stand at the elbow of this celebrated bottom fisher.”

The social history of London in the pole period is engrained in Michael’s story. Hard as life was for the working man, it was getting better. Factory laws were improving wages and increasing free time, whilst the coming of the railways gave the inner city dweller more access to both the Lea and Thames where the fields began. Angling clubs proliferated, well over a hundred during the Victorian age, and these gave the structure required to organise those massively attended matches that became part of legend. Before the clubs, too, angling had been largely unregulated, and as often done with net as with rod, and slowly conservation measures crept in. And then we have the pubs, the tap rooms where clubs met, where the draws took place and where the cups were filled and the triumphs celebrated. (How about the Lychnobite society formed in 1893 by printers at The Times newspaper? They were all night workers, and their name comes from one who sleeps by day and works by night, adapted from the Greek word for lamp.)

For decades, Michael has taken in poles battered by the storms of life and given them a new future. Some of his very many poles he has restored himself, some have been renovated along with artists like Paul Cook. These are creations of real beauty and soul. Their colours are perfected by age, their whippings, delicate and colourful, their spacings as unique to their makers as our fingerprints are to us. He makes it clear that poles are fine examples of folk art, not dissimilar to the flowery decorated buckets belonging to the canal people. There is no doubt that a pole in the hands of a man like Henry Wix was a deadly weapon, but even these can have their savage beauty.

This has been written as a review because this is an important book for any collector and/or angler, but Thomas Turner has also been fortunate enough to meet Michael Nadell himself very recently. You know what they say about meeting heroes, but in this case, the warmth and the love that courses through the book was mirrored in the author himself. Michael has undoubtedly enjoyed a rich, eventful, successful life, and poles have played their part in it. As the years fly by, the celebrated names of our angling past fade into oblivion, especially now as books have given way to the internet. Michael remains a link between the 2020s and an age almost forgotten, and some of the players in it. Some of you oldies might remember the name Frank Murgett, a great pole man, a great character and author of that fine little book “How To Fish The Lower Thames” (1960). As Poles Apart describes, Michael met the richly curmudgeonly Frank in the last years of the latter’s life, and the book is worth buying for those encounters alone.