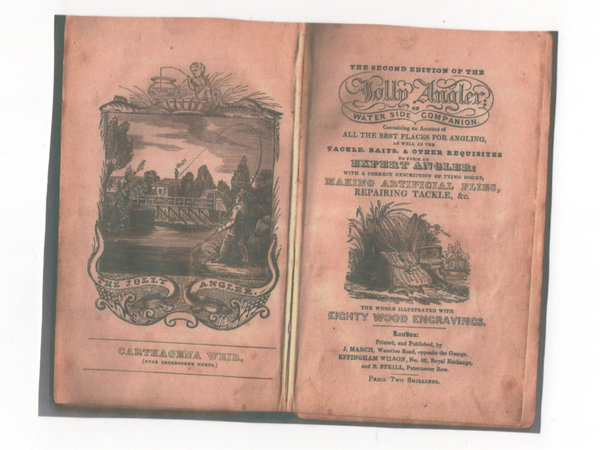

Doesn’t look much does it? Just an old notebook perhaps?

But open up the cover and this is revealed.

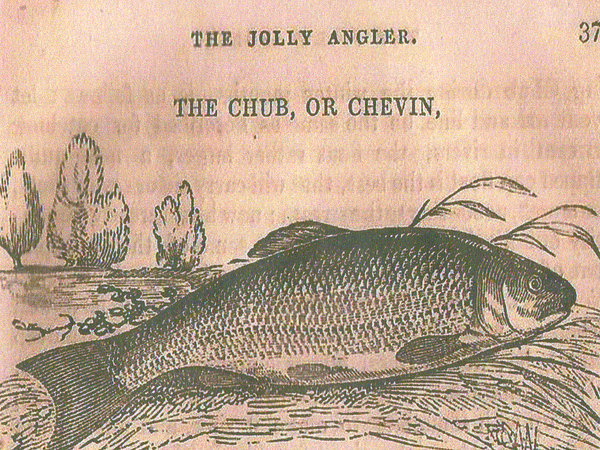

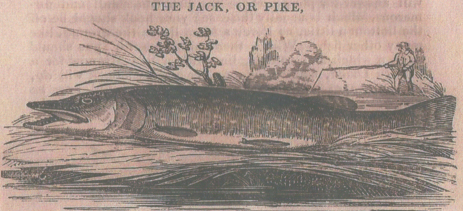

This is the second edition of The Jolly Angler or Waterside Companion, published in April 1836 and priced at two shillings.That would be around £8 in today’s money and back then the average weekly pay for a textile factory worker was around thirty shillings.The book consists of 103 pages and there are no photos but a total of eighty wood carving illustrations.

In the Introduction by the author, James March, in referring to the first edition he states: “The following work has been written with no other view than to place before the public, in a condensed form, and at a reasonable price, a body of useful information on the ‘Art of Angling’

He goes on… “The sale of upwards of a thousand copies, without the assistance of a single advertisement, or, to my knowledge, solitary criticism, has convinced me that such a work was wanted; and encouraged me to endeavour to make it as perfect as possible in this second edition”

The book was published just three years after slavery was abolished.

After the passing of Abolition of the Slave Trade Act in 1807, British captains who were caught continuing the trade were fined £100 for every slave found on board. However, this law did not stop the British slave trade. If slave-ships were in danger of being captured by the British navy, captains often reduced the fines they had to pay by ordering the slaves to be thrown into the sea.Parliament passed the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833. This act gave all slaves in the British Empire their freedom. The British government paid compensation to the slave owners. The amount that the plantation owners received depended on the number of slaves that they had. For example, the Bishop of Exeter’s 665 slaves resulted in him receiving £12,700. Can you imagine that? A Bishop with 655 slaves? There is also reference in the book to the Rights of Property under Fisheries and Fish, which quotes Chitty’s Practice of Law which was published in 1833.

“Persons maliciously breaking a dam of a fish pond or other water, which is private property, subject themselves to seven years transportation”

And further:

“Many works on Angling give instructions how to intoxicate and catch fish (a most disgraceful practise that no Angler should attempt) but, for fear the eagerness to obtain fish, possessed by some of my juvenile readers should tempt them to try the experiment, I hereby caution them that an Act of Parliament renders them subject to seven years transportation for intoxicating fish”

So, whilst slavery had been abolished (in the UK at least) deportation to the colonies was still a punishment. The author also introduces us to a Glossary of Technical Terms used by anglers which include:

Gregarious – “Fish that congregate together, and swim in shoals, such as Gudgeons, to distinguish them from those that live solitary, such as the Jack”

Landing Net – “…is a net attached to an iron or brass wire-hoop, and fixed in a stick”

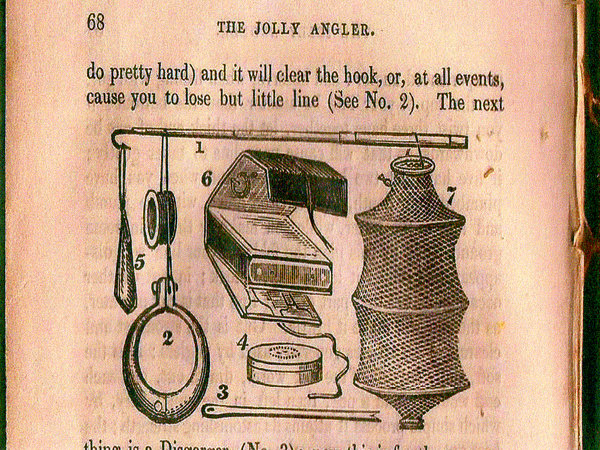

Some of the tackle in use at the time

Leather Mouthed – “those fish are called leather mouthed, that have gristly jaws without teeth, such as the Carp, Barbel, Gudgeon, to distinguish them from the voracious tribes, such as the Jack,Perch, Trout, all of which have bony Jaws, studded with an abundance of sharp teeth”

The Stickleback

The author then gives us his views on the various rivers he has fished and treats us to this regarding the River Thames near Battersea Bridge.

“We are now getting too near town to expect much sport; still there are many Roach and Dace to be caught at Vauxhall, Westminster, and other bridges, where the kind of enquiries of “What sport?” “Do they bite?” “A maggot at one end and a fool at t’other,” with occasionally a handful of dirt or a stone coming in the water or on your head, renders angling anything but an amusement”

By 1842 fishing the Thames had gone rapidly downhill though, as in Edition 5, published that year he writes:

“Refuse from the Gas Works, and other poisoness substances have killed all the fish in the river near the Metropolis”

But within a few years it was to get much worse than that. The Great Stink was an event in central London in July and August 1858 during which the hot weather exacerbated the smell of untreated human waste and industrial effluent that was present on the banks of the River Thames. The problem had been mounting for some years, with an aging and inadequate sewer system that emptied directly into the Thames. The miasma (stink or stench) from the effluent was thought to transmit contagious diseases, and three outbreaks of cholera prior to the Great Stink were blamed on the ongoing problems with the river. Surely no fish could survive such a situation and it must have been absolutely awful for the people of London to have to live with. But back in 1833 the rivers in and around London held plenty of fish, and even the East India Dock in London was producing 3lb perch.

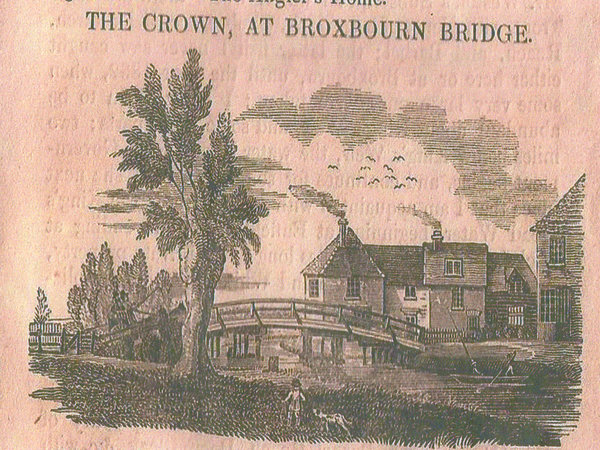

The Crown at Broxbourne today!

According to the author: “The Lea River has an immense number of fine Chub.The Lea and Colne rivers are the best rivers I know of for brain-fishing. Have ready a quantity of bullock’s brains, as well as some of the white pith out of the back bone. Throw in a little of the brains,, beat up with something to make it sink, and put a piece of the pith, about the size of a filbert on your hook”

This is the best fish catching tip of all though: “The best plan, if you are not over-delicate, is to chew the brains, and spit them out into the water where you are angling; they will sink when well chewed. I have been thus explicit on the subject here, as no other fish are angled for with brains”

And haven’t been since I shouldn’t wonder!

So what about The Barbel then? Well, we are told: “This fish is very plentiful in the Thames and Lea; I have never caught one in any other water, though I believe most rivers immediately connected with the sea contain great numbers of them, particularly in the River Tagus; there they do not grow so large as in this country, seldom weighing above three pounds, while here they grow four times the size; they feed in great numbers together, routing up the gravel with their noses like swine”

But best of all he tells us that: “They are coarse eating, something like the so-much-praised Carp; the roe is said to be un-wholesome, but I have eaten it without any ill effects, though it may act differently on other people”

I think I’ll stick to cod and chips in that case!

The author describes many other fish but I would like to finish this article with The Jack, or Pike: “They are numerous in many rivers, canals, lakes, and ponds, and are commonly caught up to ten pounds in weight, some grow much larger, and have been known to reach forty or fifty pounds; when large they are called Pike. This is a firm-eating fish during the Winter, and may be roasted or baked with a pudding in his belly”

Marion! Forget the cod and chips and peel some potatoes, I’m going pike fishing!

Eddie Benham