I have agonised over this piece for far too long and it needs to be written. My issue is that I am too close to the subject, and I have come to feel anything I might say is woefully inadequate. Hence my prevarication has lasted a week, since I walked out along the stretch with Enoka and her good friend Karen, camera at the ready. It was a grey day, but all went well, and superficially this mid-Wensum piece should not have been difficult. My problem is knowing exactly what to say about a stretch of river that looks exactly as it did in 1971, but has changed beyond recognition below the surface.

The piece of water in question lies in the mid-part of the river in that Billingford to Lyng region, and is approximately four miles in length – Enoka, Karen and I walked less than half of it during the day. Of course, I didn’t bother them with its history, and the fact that I fished the swims we came across around 150 times a year between 1971 and 1988. The vast majority of my roach over 2.12 came from this area, along with all my “threes”. I never saw a lot of anglers there during those heady years, but those that did appear caught their own massive fish. I’ll detail catches as we follow the walk, but it is my contention that there has never been such a proliferation of big fish from such a short length of water in the history of roach fishing. Avon boys will be shifting uncomfortably at this assertion, and I guess it will be a talking-point that can never be proved either way. As we all know, those years also saw the start of the river’s decline to the low point it has now reached – goodness knows what I would have caught had I started as a toddler.

10.00am… Enoka and I start at Goliath on the upper end of the beat in question whilst we wait for Karen to arrive. It is moderately pleasant though heavy drizzle is expected. The endless winter rain has left the meadows awash with water, just as a flood plain was always designed to operate during the winter months. The swans are enjoying the chance to browse on the wet, rich grasses, along with a flock of cantankerous geese from a nearby farm. However, despite such perfect conditions, there is little else to watch. A heron. Two airborne cormorants. A clutch of waterhens, but none of the waterfowl or wading birds that would have been here in profusion half a century ago. The swim itself has altered subtly too: the bend and accompanying slack are not as apparent as they were when massive roach haunted the swim. Then it was six feet deep, clean-bottomed, at the bottom of a long riffle, but mercifully slack in even high water conditions. It was a sure bet for “twos” from 1973, when I first fished it, but between 1987 and 1988 it went out with an explosion of “threes”, including my 3.10. I was never sure of the fishing rights. I was challenged by a keeper in 1975 and told I could fish on, telling anyone in the future Cliff had okayed me. When I tried the swim again briefly – and unsuccessfully – in 2009 I mentioned Cliff to an angry landowner, only to be told he had died twenty years before.

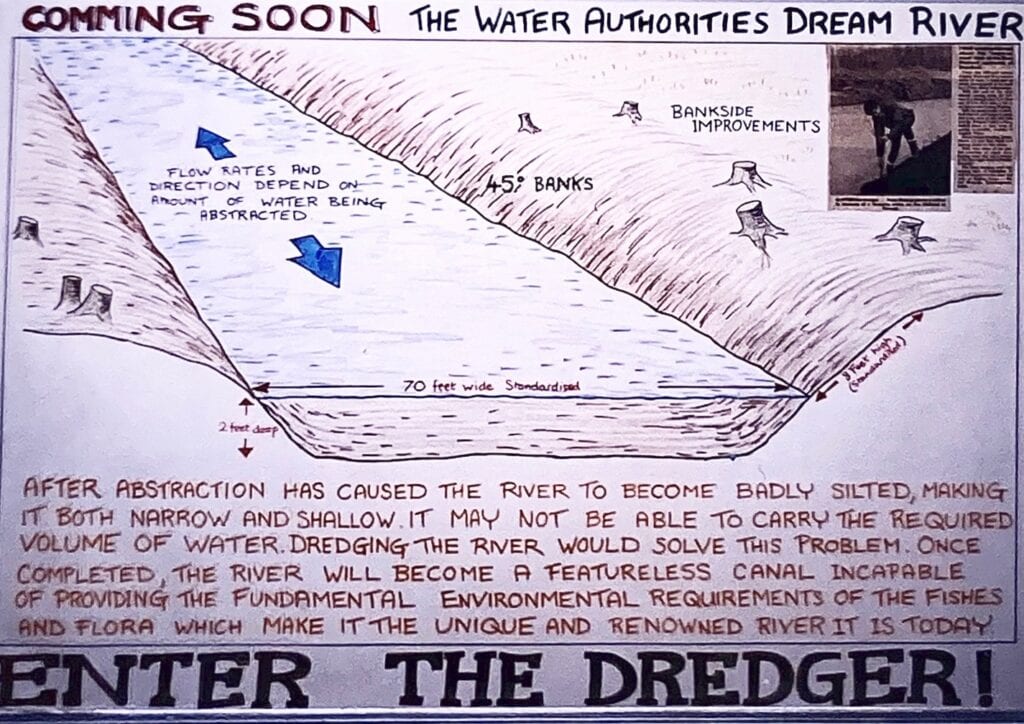

11.00am… Karen has arrived and we walk downstream, passing the Big Bend. There is fine rain in the air, and a very damp barn owl is out early looking for voles, worms, whatever it can find, I guess. The Big Bend always was a smaller version of Goliath, another bend and slack beneath a quick run. 1972-4 saw its heyday, and a bag of four roach between 2.10 and 2.14 in a mere half an hour always stands out for me. By 1977, the dredgers had made their way along it, and it never produced again to my knowledge. What is both tragic and significant is that the three of us are walking along a steeply raised river bank, a formation made nigh on half a century ago by that dredger, and the ones that relentlessly followed it, dumping gravel from the water onto the land. We are in effect walking along the one-time river bed.

half a century ago and still in evidence to this day

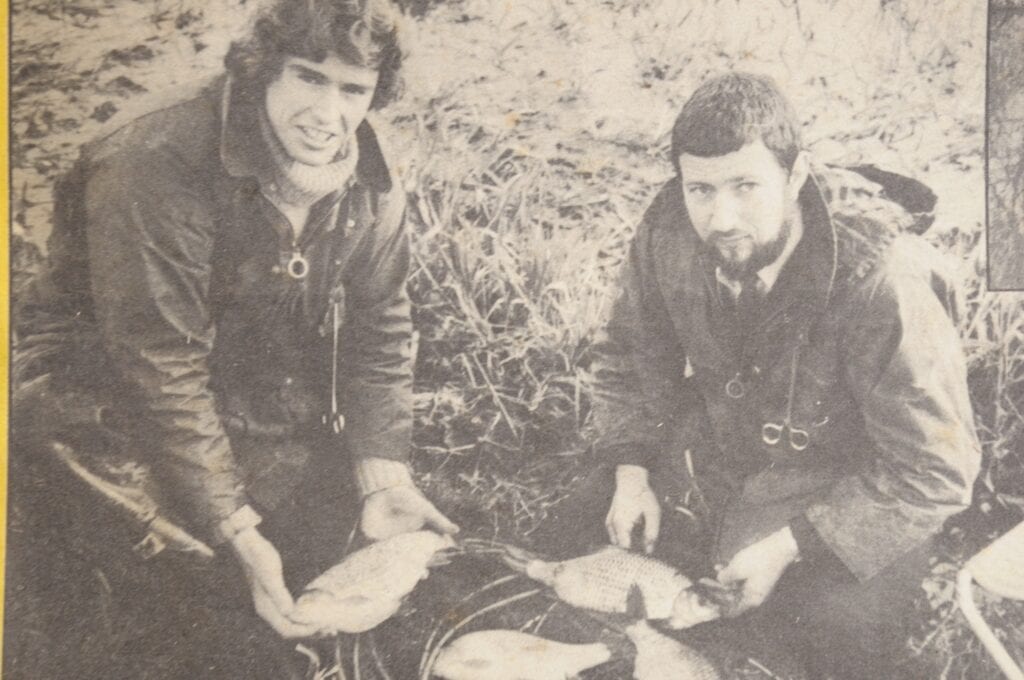

11.20am…. We are at Church Run where the river narrows somewhat, deepens and retains the air of a natural river. The dredgers never really affected this 400 yards, simply because they couldn’t crash their way through the graveyard to the river bank. God works in mysterious ways. Today, the wet is kept off us by trees on the far bank, as it was back then. The Run was always a good place to settle in a wind, and trotting produced endless fish, though not always the big ones. John Wilson and I fished it one cold December morning in 1975 for an Anglers Mail special. By the time the photographer arrived, JW was in a grump because we had “only” had five “twos” to 2.08. The guy with the camera looked at him wonderingly but that is how it was in the day.

11.30am… Now we reach the swim I knew as The Alder, the place getting on for 50 years ago where I had my first run of colossal fish. It was at The Alder that I got tired of being broken on maggots and 2lb bottoms, and moved to bread and 3-4lb Maxima straight through. My first fish here weighed an extraordinary 2.13, and I was besotted with the swim for nigh on two decades. What made it so good? The cover granted by the old, overhanging alder? The thick marginal weedbeds leading 100 yards to the swim itself? The fact the depth dropped from an average of four feet to six feet plus? Or simply the fact that I piled bread in night after night? I remember a biting cold dusk one January in 1975 (I think) when an upstream Easterly was holding the flow back. A piece of crust floated up from the handful of mash I had thrown out minutes before, and a roach nudging “three” slurped it from the surface at my feet. Today, there wasn’t much to show the girls. That alder had fallen to the dredger a long while back, and the copse where a badger sett had been established was long gone. The animals had always kept me amused in the cold, fishless hours, and soon learned to come to me as a source of bread and peanuts.

11.45am… We stand at the head of what I called Hendry’s Run. It was here I watched Norfolk roach maestro Jimmy Hendry take a 2.11 fish on maggots very first trot down. That was the way of it all those years ago. In the dark, I legered flake with butt indication in the slacks like Goliath and The Alder. In the day, I would trot maggots along those long straights like Church Run that sometimes were pockmarked with huge rolling roach. Today, of course, we have not seen a fish, and come to that barely any coots, waterhens or grebes. The otters have seen to them.

12.15.pm… Enoka, Karen and I stand by the stream entrance and look downriver towards a distant mill. The plain is wide, gun-metal grey and forlorn. This stretch is now private and out of bounds, but it holds one of the legendary swims, The Great Bend, where I spent over two hundred winter evenings and where I landed my first “three” at 3.02. This was the biggest slack on the whole upper river, and in the middle of the channel the depth reached an extraordinary 14 feet. I’d never been able to explain that remarkable trench in a river generally half that depth at best, but the roach loved it. A couple of muntjac are nibbling on the edge of the valley side and more cormorants plod their way over the horizon, but apart from a distant babble of rooks, there is nothing but silence. The cars are on the lane a mile away and we leave the river, a rather gloomy job done.

Walking back, I’d like to talk to the girls about the great days and what has gone so appallingly wrong in my adult lifetime… but I don’t want to be a bore. I think they appreciate the haunting beauty of the place. It was never chocolate box, but for me it spoke of more magic and mystery than I could barely contemplate. Remember, I was brought up on Northern canals where any roach was a good one, and a four-ouncer was a whopper. These Wensum fish were twelve times the size… it was like finding a UK river holding 100 pound barbel or 70 pound chub. But above all, the allure was the place, those lonely plains haunted by lapwing, skylarks and snipe, where dreams were brought to staggering reality.

What went wrong? The deep dredging led to a collapse of stocks in a way we did not recognise half a century back. In the winter floods, with all cover gone, small fish were simply swept through the mill sluice gates downriver ’till they reached Norwich, or died on the journey. Many of the spawning gravels were destroyed, and recruitment levels were battered. Moreover, dredging cut the main river off from the ditches and streams that laced the flood meadows. The mouths of these were blocked and the sanctuary they had offered generations of small roach was denied. It was though the dredgers had cut the river’s spine off from its radiating ribs and left it crippled as an environment. The evidence of this monumental act of destruction is still obvious, unsoftened by time. There have been periodic revivals, periods when small roach have returned, but predation levels have changed over half a century. The otter has comparatively newly returned but worse, it is the old tale of the appearance of the cormorant, a bird that gives scattered roach stocks in such a lonely environment no chance of re-establishing themselves. If we could stock this river with hundreds of thousands of roach and then protect them, I can guarantee (almost) we would see the old days back. But we all know this will never happen under current regimes.